Volume 1 - chapter 14 -Part 2

It may have been from the local newspaper that I discovered that the famous Josiah Wedgwood was taking on staff, so I thought, ‘nothing ventured nothing gained,’ and I took myself off to the new model factory they had built out in the country near Barlaston. The personnel officer was a middle aged lady who was well spoken and dressed in tweeds. She had an office in a small detached building which meant that I did not enter the main factory, though I could see it was very modern with large areas of glass to allow good lighting. I had an extensive interview with the nice lady, during which she asked me for details of my hobbies and my home background. I was glad of this because my lack of educational qualifications was all too obvious, and for the first time in my life I became conscious of the importance of such things.

At the end of my interview the lady told me that there was a job in the decorating department for which she thought me suitable, and it was mine if I wanted it. I was to be a general factotum, but in time I would learn the various decorating processes, and could eventually become a departmental manager. It sounded good to me so I accepted and arranged to start the following Monday. Today I look back with the benefit of hindsight, and with much more understanding of the way things were, but at the time I had a much different impression of my situation. I had a job with a famous company, I had prospects, there appeared to be no need for reading, writing, or arithmetic, I would be able to prove my worth without any certificates or qualifications. In reality I was just to be a boy in the factory employed to fetch and carry, I was not a member of the staff, and I had no artistic skills to offer. It is certain that the kind lady, who gave me a job, had no illusions about my future prospects, or the lack of them.

The pottery industry was notorious for its unhealthy working conditions and minimal wages. Employers made huge fortunes at the expense of their workers who were often talented and skilled. Apart from those who cast things of beauty on a spinning wheel, there were dippers that applied the glaze, not a simple task; there were engravers that created pictures on copper plates, used to print the decorations applied to the tableware and other items of clay. There were also the myriads of working girls that painted and decorated with superb skill and great artistic talent, creating things of beauty that made a fortune for the people who employed them. It is hard to believe that all these workers provided their skills for a measly wage, while in other situations artistic skills such as theirs commanded handsome reimbursement in other circumstances. At least where Wedgwood was concerned an effort had been made to provide healthier working conditions, though the wages they paid were very little better than the wages offered by others in the industry.

The modern model factory where I took up my new employment was about 5/6 miles south of the city, set in a country setting. Much of the surrounding land was owned by the Wedgwood family, which ensured that it would remain the way they wanted it to be. The location had been chosen with great care with both the railway and canal running passing close to the factory. A short walking distance away they had built their own little railway station called Wedgwood Halt, and it was here that many of the workers arrived for their days work. A large proportion was from the Potteries, but there was also a small number that came from Stafford and places to the south. A row of houses had been built for those who were valued by the company, and a short distance to the east was a long narrow artificial lake which had been stocked with a variety of fish, including the anglers delight, the Pike. It was an impressive layout, and for most of us who came from the smoke laden and grimy city, it was a delight.

With the winter approaching I began my new employment by joining those who commuted by train each day. I would leave the house about 7am and catch a bus to Stoke railway station; about 7.40am the throng of workers would board the Manchester to Birmingham train which deposited us at Wedgwood Halt ten minutes later. We usually had ten minutes to walk to the factory where we clocked in at 8am, and here in lay a problem. Quite a crowd of us left the train, and at the end of the platform there was only a small picket gate through the fence that surrounded it. Those that brought up the rear would sometimes miss the 8am dead line for clocking on, and so there was always a dash for the gate. The young chaps in the crowd being short on sense would open the carriage doors before the train had stopped and would take a running jump, using the platform as a sprint pad.

With youth and agility this worked well enough, so I became one of the jumpers, trying with the others to be first through the gate. It was a risky thing to do, which was highlighted for me one winters day when we arrived on the train and did our usual thing. It had snowed and in the night the layer of snow had frozen into a sheet of ice, when I landed on it at speed my feet skidded from under me and I landed flat on my back. The other two or three fools who followed my example also went down like so many skittles, though we were lucky enough to get away with just minor bruises and no major injuries. I was lucky that day because I was wearing the thickest overcoat I had ever had, which cushioned me from the impact. It was in fact my father’s officers great coat, which had been dyed a dark brown and had civilian buttons attached. It was a quality coat and I thought very smart, I always felt good in it, and on this day it proved a benefit to me in a way I had not anticipated.

A tableware factory, or pot bank as we used to call them, was a women’s world with about 80% of the work force being female. I had little experience of the opposite sex to this point in my life, and was to find that working with so many women a revelation, and an education. My immediate boss was the manger of the painting and decorating department, which employed maybe fifty girls. There were those who painted in enamel paint, mostly on prints which had already been applied, and then there were the free hand painters who worked on designs other than printed ones. There were other groups of girls who did work with a brush; they were situated in other parts of the factory. There were liners who worked with a wheel, there job was to put colour bands and lines on various items by spinning them on the wheel and applying the brush to the spinning plate or saucer. It sounds easy, it looked easy, but it took much skill to do it correctly.

There were the guilders that did the same sort of thing in gold rather than colour, and there were all the other departments as well. There was a man who was manager of the printing department, and a middle aged lady who managed the burnishing department. In charge of all the painters and decorators was a Mr Reid, and was the one to whom I looked for my orders; most of the time Mr Reid left me to my own devices knowing that I would be kept busy by the demands of everyone who worked in the decorating department. My main job was to move the ware as required, from department to department, and finally to the warehouse where the finished product was stored. Everyone could use my services, but I did have the advantage of being free to roam the entire factory without looking out of place, or being asked what I was doing or where I was going.

Nearly everything was moved in trays with sides that were about eighteen inches high, or on steel racks which held wooden boards on which the hollow ware was placed. Both these receptacles could be picked up on a hydraulic jack, which had small wheels. The forks of the jack were pushed under that container, which was lifted clear of the floor so it could be wheeled easily from place to place. I was not supposed to spend my time loading and unloading, but I often earned myself considerable good will by helping to do so. My willingness pleased everyone; it was not difficult for me because I was obliging by nature. This gave me an advantage when I did things that were against the rules, often people would turn a blind eye because I was in their good books. For example, the heavy steel trolleys were supposed to be moved only at a walking pace, but when they were without a load, they could be used like a scooter. With their smooth running wheels they would glide along and could be accelerated to a running pace. I soon became expert at scooting around at a very fast pace indeed, and was often seen doing so, though no one every told me off for doing it. There were no brakes on these machines of course, and to stop them the trick was to spin the steering handle, which had a small double bogie on the end of it. This had a braking effect, and I soon became expert at stopping within a whisker of things.

Because I went out of my way to be helpful, those that wanted me would show some patience if I was not around. This was very helpful because I often stopped to watch what was happening somewhere in the factory, and I had time to watch and learn without worrying that someone was getting steamed up looking for me. One place that attracted my attention was the workshop where a new glaze dipping machine was being developed at the time. In the past the only way to apply a glaze to pottery was for a skilled dipper to do it by hand. Now a machine was being developed that would do it automatically, though it was proving difficult to get it to work to perfection. The glaze had to be applied to an article thinly and evenly, with no thick deposits or areas lacking in glaze at all. The machine was designed with a circular conveyor with slender prongs on which the pottery was placed. Turning slowly the conveyor carried the items through a short tunnel which contained jets that sprayed the glaze. The excess liquid fell into a sump from where it was pumped back into the spray tanks to be used again. It was a simple idea that should have been straight forward, but when I left the factory some six or seven months later, the engineers had still not made it work to perfection.

My time at Wedgwood’s was only short, but it was not all dull and boring, there were moments of interest and excitement. There was the strike when the work force downed tools for better pay and other things that I never knew about. The management kept vital parts of the factory going, like the kilns, and other such things. I was told by Mr Reid that I was not a member of the union and so should keep working, which I did, though it did not make me popular with my fellow workers.

There was the day I was sent to get the figure of a bull from the sample room, where samples of just about everything that Wedgwood had ever made were kept. These originals were priceless, and so was the bull which was covered in the signs of the zodiac, and was about 9/10 inches long. I had to climb a flight of stairs on my way back to the decorating department, and near the top the rubber heel on my shoe came loose and caught on the edge of the step. I fell with a crash knowing that the only thing that mattered was the precious bull. Clutching it tight in my arms I curled up tight and bounced like a rubber ball, saving the bull but suffering a number of bruises.

Some of the products made were very valuable indeed, so much so that even a single item if rejected, or not required by the buyer, was destroyed. I often got the job of destroying these lovely pieces of work, and could never see the sense in it. Why not sell them I thought, even if only to members of the staff, they would at least earn something and would not be entirely wasted. On one occasion there was a consignment of wall plaques being made for the ‘Big Game Club of South Africa’. They were almost ready for delivery, when a cancellation arrived, and several hundred of them had to be destroyed. They were the most beautiful things you ever saw, being plates about ten inches in diameter each with a marvellous picture of a wild animal in the middle. They were all there, lions, elephants, giraffes, every big game animal, and around the rim of each plate was a thick rich decoration in heavy gold. I cannot imagine what they would have been worth, but it must have been hundreds of pounds for each one, and I stood at the rubbish chute with a hammer, breaking each and every one of them before throwing the pieces down into the rubbish wagon below. Did they ever try and recover the gold that had been wasted? They certainly saved the rags that the guilders used to clean their brushes; these rags heavily impregnated with gold residue were sent back to the suppliers so that they could be burnt and the gold recovered.

There were two or three boys like myself who fetched and carried, but I was the only one working in the decorating department. We were the only employees who were allowed to move about the factory, everyone else had their place of work and were not expected to leave it. The girls of my department were considered of a better class than those who worked in what we called ‘The Clay End.’ We heard stories about these ‘Amazons’ of the dirty end of the factory, which made me more than happy that I did not have to go into their territory. One day a rumour winged its way around the workers, that the boy doing my job in the clay end of the factory, had been found in one of the remote stock rooms. He had been tied up; his trousers removed, and wet clay packed around his private parts. You can imagine how I felt when a couple of days after this story had made its rounds, I was instructed to go to that same stock room to collect a replacement plate for one that had been damaged in the firing process. Away I went through the glazing department, past the ovens where the pieces formed from the wet clay were fired into biscuit. In the vicinity of the casting and moulding departments, there was a lift which I had to take down into the bowels of the factory where the stock rooms were.

I was seen entering the lift, and in a flash two young women were into the lift with me. They were big brawny girls with arms like weight lifters, and I knew immediately that they meant me no good. As the lift began to descend they made their attack, one grabbing me from behind, while the other pressed the stop button for the lift. To them it might have been a joke, but to me it was deadly serious, and for the first time in my life I found myself using violence against the opposite sex. Their intention was to shame and embarrass me, but for a young man that would have been the ultimate in degradation, and I would have died first. It is a memory to laugh at now, but at the time I took it very seriously. Breaking from their grasp I punched like a boxer, and I was not gentle about it, which soon made them give up on their attack.

It was not often that I left my usual work area, but when I did there was often an adventure around the corner. At the other end of the factory the social structure rose with a superior type of worker in the warehouse that housed all the finished products. At one end of this warehouse was a door into the office wing where clerical people moved in a world of their own, and management had their offices. This sacred domain was off limits to the plebs in the factory, and I for one never passed into those hallowed halls. I did occasionally take items into the finished warehouse, and on one such occasion I came to the attention of the haughty Mr Smith, who was manager in this superior place of work. He may have been in need of an extra pair of hands at the time, so on observing me he promptly instructed me to carry out some work for him. I could not refuse such an august personage of course, but he was a pompous individual who was far from popular, and I was not going to help him if I could get away with it. In reply to his instructions I said very politely that before I began the work he had given me, I had to report to my immediate superior Mr Reid to let him know where I was.

Being mostly foot loose and fancy free my claim to need Mr Reid’s permission was a fabrication, but the superior Mr Smith had no option but to let me return to my own department to get permission to work elsewhere. I knew that all the departmental managers were empire builders, and jealous of their own authority, so it came as no surprise to me when Mr Reid reacted with great indignation. Accompanying me to the place where Mr Smith awaited my return, my boss waded right in with all guns blazing, and I stood to one side while these two giants of the factory floor vented their spleen. Having broken the rules Mr Smith was bound to lose this dispute, so I was free to go my way without having to work for him, I was never asked again to do work outside my own department.

Wedgwood’s did not pay well, but they did many other things to make the work place a more enjoyable place to be. For example, they had an excellent canteen which was situated in a separate building alongside the main factory. At one end of the main eating area was a special seating arrangement for staff and management, at the other end was a stage for entertainment, which were organised on a regular basis. Once or twice a week the diners would be entertained by a talent show, made up of employees who had something entertaining they could do. The personnel office organised these concerts, and they advised every entrant that the best performers would be selected for a grand show, which in a few weeks time would be broadcast on the radio. During the war the BBC had introduced a daytime broadcast called ‘Workers Playtime,’ which toured the factories of Britain, and these dinnertime concerts had proved very popular indeed. Because they were liked so much the show was continued after the war, and it was to be broadcast from the Wedgwood Canteen a few weeks after I began to work there.

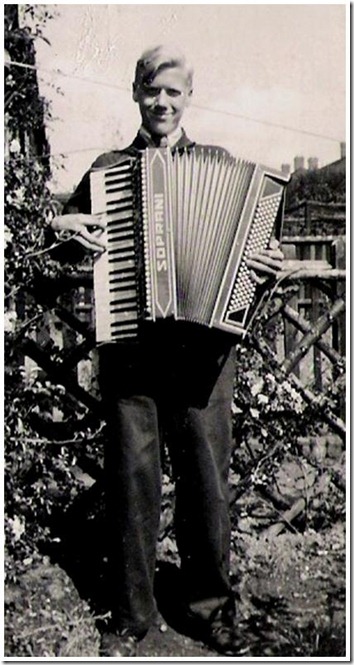

It should have come as no surprise when the Personnel Manager, the lady in the country tweeds, sent for me one day, and after pointing out that my records showed I played a musical instrument, asked me if I was willing to appear on their concert in the canteen. My preference was to play for my own pleasure but under the circumstances I had little option but to agree. I duly appeared on the stage, and played a selection of popular songs of the day. My efforts were received with great enthusiasm, the favourite melody being ‘Blue Moon,’ which had everyone singing, and shouting for more. Needless to say, I was oneeveryone singing, and , and played a selection of popular songs of the daymentedgewood h were organised on a regular of the chosen few who were asked to perform for the radio broadcast a few weeks later.

No longer was I a nonentity, now everyone knew me, and most had friendly things to say, which made life much more enjoyable. Most of the clerical staff we males in those days, and these socially superior beings had formed a male choir which was funded by our employers. The leader was a gifted pianist who did not work for the company, but he knew music and trained the choir to an impressive standard. One of the results of my appearance on stage was that one of the staff, who was in the choir, approached me with an offer to join their happy throng, and this I did. For me it was an added pleasure to a life that seemed to have little to offer, we were given time off from work to practice in the canteen, which had an excellent grand piano. I enjoyed the music, singing second tenor, because my voice had broken and was a little low for the top tenors, but not low enough for the baritones. We were not bad, though I say it myself, and our rendition of ‘The Soldiers Chorus’ was great stuff, or so I thought. When I think back, I have to confess that almost as much as the music, I enjoyed the refreshments provided by the canteen. My particular favourite was the jam tarts that came with the fresh made sandwiches, and of those my particular favourites were the lemon curd tarts.

Christmas 1948 was not far away, and a further feather in my cap was to be my appearance in the concert to be held at the Trentham Gardens Ballroom, which had been hired by Wedgwood’s for their grand company ball. The star of the show was a famous radio personality Richard Murdoch, but according to the rumours around the factory, my accordion and I were almost as popular, because I was willing to play requests on demand, which pleased everybody. On the day of the big event I was told to report to the personnel office, where I was placed in a taxi and dispatched to Trentham. The decorating department were informed that I would not be working that day; I was required to stand guard at the ballroom. It is true that the decorations, an impressive display of flowers and potted plants were being installed during the day by Wedgwood’s, but I had no part to play in this arrangement. All I did was sit around and wait for the celebrations to begin, and looking back now I realise that I was being treated as someone special, though the penny did not drop at the time. The dinner, dance, and concert were a great success, and I have attended few such grand events since.

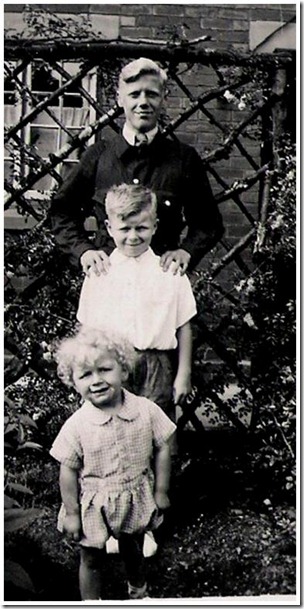

Before I turn my back on my time at Wedgwood’s it might be of interest if I mention one or two people that became my friends, but who passed from my life when I departed the scene. Firstly there was a young man named Les Booth, who was a typical working lad two or three years older than me. Les was a ‘Place Setter’ his job was to place the ware to be fired in the electric tunnel kiln, and then to remove it when it emerged at the other end of the tunnel. There were a number of these ovens in the factory which were new, having been installed by the Swiss Manufacturers only a few months previously. Les was a hard working lad, with no bad characteristics that I could see; he was what I would describe as ‘Salt of the Earth.’ In a very short time we became firm friends, and when I was invited for another of my regular holidays at my Aunt’s hotel at Rhyl, I invited Les to share it with me. My fondest memory of him was an occasion when we were walking along the promenade with my Aunt and Uncle, on a hot sunny day, and he was asked to get ice-cream wafers for all of us. Off he dashed through the busy throng, then skidding to a halt some 20/30 yards away, he turned and yelled at the top of his voice: “Dust want four penny uns or sixpenny uns?” Well, the look of embarrassment on my Aunt’s face was something to behold.

Next I would like to mention a young lady named Anne, who was one of the most talented artists I have ever seen. She came from Stafford and worked as one of an exclusive few who painted the famous Wedgwood plaques, which displayed a hand painted picture of fruit displayed in a bowl or other such receptacle. The work that she did was perfect and had she been a famous artist her work would have commanded considerable sums of money, but like everyone else who worked at Wedgwood’s she worked for just a modest wage. It was my job to supply Anne and the others with the plaques to be painted, and before long she was looking forward to my visits. She would encourage me to stay and talk to her, while she painted, and this I was more than ready to do. She was a lovely person with a gentle nature, and I liked her very much, it was also an attraction to watch her work. She painted quickly and with confidence and it was an endless source of fascination to watch the picture she was working on take shape in front of my eyes. Seeing my interest and admiration she occasionally amazed me with a demonstration of her ambidextrous skill, when she would take up a brush in each hand, and paint with both hands simultaneously. Anne was a well built girl of about 20 years of age, and though I now suspect that she had been attracted to me as a member of the opposite sex, I for my part was never physically attracted to her.

The world in which I worked was a female world, but they had never played a part in my personal life. Women were all around me, and I was happy with this situation, they were pleasant to be with in the most part, but I never felt any great attraction to them until now. I suppose it was bound to happen eventually, and one day I realised that a young lady was having an effect on my feelings and emotions that I had never experienced before. The young lady was about 19 years old and her name was Peggy Derbyshire. She was slim and very pretty with long wavy black hair; being the summer of 1949 she wore full summer skirts of bright colourful designs, and white diaphanous blouses which were often off the shoulder, and very fetching. I never knew what her official position was but I knew she was a member of the office staff, and might have been the secretary to the senior manager who ran the whole decorating department.

Part of her duties was the supervision of work done by the painters; she would collect their work sheets and calculate their earnings. I would sometimes help her to make her collection, and then one day said she would take advantage of a large empty basement where she could work in peace and quiet away from the office. She asked if I would take a chair down for her, and on later occasions, I would fetch and carry for her at her request. Gradually I spent more and more time with her in the basement, where I would stand at her side mostly in silence, just looking at her profile, the texture of her skin, and the slenderness of her neck. She hardly seemed to recognise my presence, and we spoke very seldom, and though my heart would be thumping like a drum, we never touched or did anything of an intimate nature. We were not secretive about our friendship, spending the lunch hour together walking in the sun outside the factory, and even holding hands in public.

If I had remained at Wedgwood’s for any length of time, there is no doubt that Peggy and I would have grown closer and more intimate, but it was not meant to be. She was several years older than I was, and told me that she had a boy friend at Stafford where she lived; in fact I seem to recall that she was engaged. Then one day she asked me whether I wanted her to be my girl, and if I did, she would finish her other relationship. Of course I desired this lovely girl, but I was just a silly mixed up teenager, who felt amongst a tumult of emotions some guilt about the young man from whom I was stealing this beautiful girl. It is strange the way fate conspires against us, and then offers a solution to our dilemmas. That weekend a message arrived at home offering me a job with my Uncle Bill in his auto-engineering business; I would have the prospect of living by the sea with my aunt and uncle, along with the security of a skilled job learning to be an engineer. I had never in my life felt such confusion about what I should do, but even at such a young age I knew that a relationship with the lovely young woman at work would upset so many lives, it would not be a good thing for either her or myself.

The following Monday I told my sweetheart that I was required to leave my job and move away from the Midlands, and the same day I handed in my resignation. I don’t know why but the friendly personnel office was not involved in my resignation, it was dealt with by the decorating manager. I had never met him until now, and wished I had never met him at all, when he came to see me in a very unfriendly manner, and told me that I would have to work a longer notice before I could leave. My resignation had been written by my father, so the belligerent manager wrote a reply to him which I duly delivered. Being in a sealed envelope I did not get to read it, but I believe it was not couched in very friendly terms, and to make matters worse, he had written the note in red ink, which was considered to be in the worst possible taste. My father’s reply was short and to the point, though again I never got to read what he wrote. I do remember taking his reply to the manager’s office and standing in front of him while he read it. The colour of his face, and the expression on it, changed several times during the few moments that it took him to read it. Whatever the contents, my father’s reply was effective, and I worked only one week before leaving.

On my last day Peggy came to me and handed me a small gift to remember her by. It was a hand-stitched verse in a frame with a picture of a sprig of heather above it. The verse went something like this

A piece of sweet heather

To remind you each day,

To help you remember

A friend far away

This verse had a place on the wall of my parents lounge for many a long year, but I don’t think anyone but me knew where it came from or why it was there. I shall never forget this young woman who was what you would describe as my first love; though it is somewhat amusing in this modern day and age, that I could think of her in this way, and yet I never kissed her not even once.